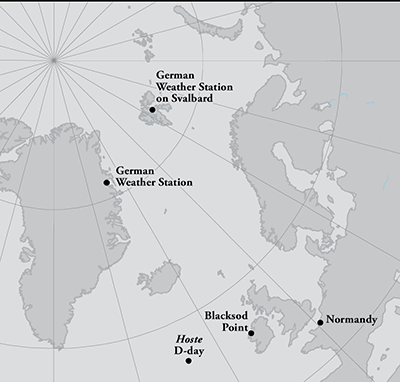

On August 22, 1942, as the Allies were two months from launching their drive to liberate Nazi-occupied Europe with landings in North Africa, the German weather ship Sachsen, commanded by Lieutenant zur See Hermann Ritter, sailed from Tromso in Norway. Despite gales, high seas, and fog, five days later the vessel pitched and rolled its way into Hansa Bay south of Shannon Island about midway up Greenland’s east coast.

As planned, soon the Sachsen was frozen fast. Ritter sent half the men ashore with materials to construct a hut. Cables were stretched across the ice to provide telephone service and electricity supplied by the ship. The crew stepped the boat’s mast, and with torches, cut down its superstructure. Snow was mounded around the hull for added insulation and so that, when viewed from the air, the ship might resemble a hummock of sea ice. Transmission of weather reports began in late September.

Though he was a former sea captain and had hunted extensively on Spitsbergen, Ritter was a bit of an odd choice for command. He was as at home with books on philosophy and religion as he was helming a trawler through the iceberg-infested East Greenland Current. Deeply Catholic, he opposed any killing that was not absolutely necessary, which was why the Gestapo vigorously opposed his appointment. After he was found in his cabin reading a book by a Jewish author, rumors doubting his loyalty began to circulate among his crew.

Seven hundred kilometers to the south, the Sledge Patrol, a group of fifteen Danes, Norwegians, and Eskimos, was headquartered at Eskimoness. Its mission was to root out German weather stations while making and reporting weather observations of their own. They divided up into teams of three or four each with a sledge hauling gear and food. Their armament was rudimentary to say the least. Instead of submachine guns like the Germans, they carried only bolt action hunting rifles.

Having holedCooped up during the long Arctic night, Ritter’s men were plagued with cabin fever. As polar dawn broke over Ritter’s camp in 1943, his men went hunting for fresh seal or bear meat to augment their boring rations. A Sledge Patrol team came across their footprints in the snow. Approaching a cabin used by transient hunters, they were astounded to see two men flee into the hills. Inside, they found a German uniform jacket hanging from a peg. They thought they’d encountered the leading elements of a large party of Germans.

The escapee altered Ritter who immediately launched an attack. Thus began an odyssey of skirmishes between German and Danish weather parties. Reluctant to kill the leader of the Sledge Patrol, Ritter captured him and ordered him to help him look for a new site for a German weather station. During the trek, the Dane apparently played on Ritter’s pacifist leanings. A few weeks later, the pair arrived at Scoresbysund where Ritter became an Allied prisoner of war and was free to read philosophy until repatriated at war’s end.

Eight hundred miles to the north and east of Greenland lies Spitsbergen, the western most island of the Svalbard archipelago. In September 1943, bird watching, not bird hunting, cost the life of another German officer on a meteorological mission. Lulled by an idyllic afternoon, Kapitänleutnant Otto Köhler decided to sunbathe in a secluded vale and photograph birds not far from the weather station at Signehamna. Shirtless, he was surprised and shot by a party of four Norwegians. There being no medics anywhere nearby, the Norwegians had little choice but, in an act of mercy, to blow out his brains.