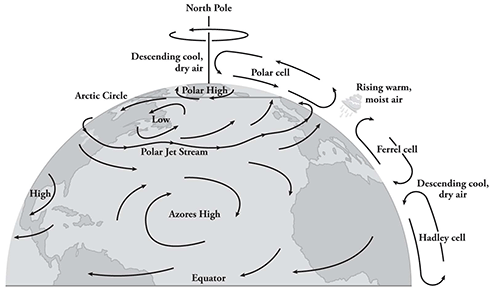

In the northern hemisphere, weather systems move from west to east. Over the North Atlantic, they are dominated by two more or less permanent meteorological high-pressure zones, one centered over the North Pole and the other between the warm Azores and Bermuda. Along the southern boundary of the Polar High, the sinuous jet stream races from west to east bringing with it wind, cloud, and rain. When the jet stream is forced north by the Azores High, mild weather prevails over the south of England and Normandy. When the Polar High drives south, storms plague the English Channel.

In the northern hemisphere, weather systems move from west to east. Over the North Atlantic, they are dominated by two more or less permanent meteorological high-pressure zones, one centered over the North Pole and the other between the warm Azores and Bermuda. Along the southern boundary of the Polar High, the sinuous jet stream races from west to east bringing with it wind, cloud, and rain. When the jet stream is forced north by the Azores High, mild weather prevails over the south of England and Normandy. When the Polar High drives south, storms plague the English Channel.

Knowing the location of the areas of calm and storm was absolutely essential if the forecast for D-day were to be reliable. To find out, the Allies and the Germans dispatched teams of meteorologists to the east coast of Greenland and Spitsbergen. Each side hunted the other’s weathermen mercilessly in the biting Arctic night. Both sent weather ships into often stormy seas under orders to send reports at least once a day and sometimes more frequently. Long-range bombers, outfitted with weather instruments, flew tedious solo flights out over the empty ocean. Fraught with peril, taking weather readings in the North Atlantic was at once a meticulous business and routinely mind-numbing.